Libraries, archives and museums have a long history of participation and engagement with members of the public. I have previously suggested that it is best to think about crowdsourcing in cultural heritage as a form of public volunteerism, and that much discussion of crowdsourcing is more specifically about two distinct phenomena, the wisdom of crowds and human computation. In this post I want to get into a bit more of why and how it works. I think understanding both the motivational components and the role that tools serve as scaffolding for activity will let us be a bit more deliberate in how we put these kinds of projects together.

The How: To be a tool is to serve as scaffolding for activity

Helping someone succeed is often largely about getting them the right tools. Consider the image of scaffolding below. The scaffolding these workers are using puts them in a position to do their job. By standing on the scaffolding they are able to do their work without thinking about the tool at all. In the activity of the work the tool disappears and allows them to go about their tasks taking for granted that they are suspended six or seven feet in the air. This scaffolding function is a generic property of tools.

All tools can act as scaffolds to enable us to accomplish a particular task. At this point it is worth briefly considering an example of how this idea of scaffolding translates into a cognitive task. In this situation I will briefly describe some of the process that is part of a park rangers regular work, measuring the diameter of a tree. This example comes from Roy Pea’s “Practices of Distributed Intelligence and Designs for Education.”

If you want to measure a tree you take a standard tape measure and do the following;

- Measure the circumference of the tree

- Remember that the diameter is related to the circumference of an object according to the formula circumference/diameter

- Set up the formula, replacing the variable circumference with your value

- Cross-multiply

- Isolate the diameter by dividing

- Reduce the fraction

Alternatively, you can just use a measuring tape that has the algorithm for diameter embedded inside it. In other words, you can just get a smarter tape measure. You can buy a tape-measure that was designed for this particular situation that can think for you (see the image below). Not only does this save you considerable time, but you end up with far more accurate measurements. There are far fewer moments for human error to enter into the equation.

The design of the tape measure has quite literally embedded the equations and cognitive actions required to measure the tree. As an aside, this kind of cognitive extension is a generic component of how humans use tools and their environments for thought.

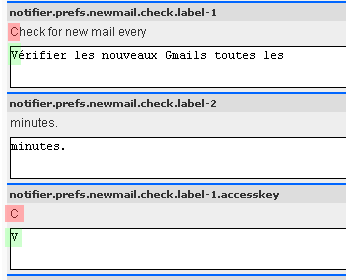

This has a very direct translation into the design of online tools as well. For example, before joining the Library of Congress I worked on the Zotero project, a free and open source reference management tool. Zotero was translated into more than 30 languages by its users. The translation process was made significantly easier through BabelZilla. BabelZilla, an online community for developers and translators of extension for Firefox extensions, has a robust community of users that work to localize various extensions. One of the neatest features of this platform is that it stripes out the strings of text that need to be localized from the source code and then presents the potential translator with a simple web form where they just type in translations of the lines of text. You can see an image of the translation process below.

This not only makes the process much simpler and quicker it also means that potential translators need zero programming knowledge to contribute a localization. Without BabelZilla, a potential translator would need to know about how Firefox Extension locale files work, and be comfortable with editing XML files in a text editor. But BabelZilla scaffolds the user over that required knowledge and just lets them fill out translations in a web form.

Returning, as I often do, to the example of Galaxy Zoo, we can now think of the classification game as a scaffold which allows interested amateurs to participate at the cutting edge of scientific inquiry. In this scenario, the entire technical apparatus, all of the equipment used in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the design of the Galaxy Zoo site, and the work of all of the scientists and engineers that went into those systems are all part of one big hunk of scaffolding that puts a user in the position to contribute to the frontiers of science through their actions on the website.

I like to think that scaffolding is the how of crowdsourcing. When crowdsourcing projects work it is because of a nested set of platforms stacked one on top of the other, that let people offer up their time and energy to work that they find meaningful. The meaningful point there is the central component of the next question. Why do people participate in Crowdsourcing projects?

The Why: A Holistic Sense of Human Motivation

Why do people participate in these projects? Lets start with an example I have appealed to before from a crowdsorucing transcription project.

Ben Brumfield runs a range of crowdsourcing transcription projects. At one point in a transcription project he noticed that one of his power users was slowing down, cutting back significantly on the time they spent transcribing these manuscripts. The user explained that they had seen that there weren’t that many manuscripts left to transcribe. For this user, the 2-3 hours a day they spent working on transcriptions was an important part of their day that they had decided to deny themselves some of that experience. For this users, participating in this project was so important to them, contributing to it was such an important part of who they see themselves as, that they needed to ration out those remaining pages. They wanted to make sure that the experience lasted as long as they could. When Ben found that out he quickly put up some more pages. This particular story illustrates several broader points about what motivates us.

After a person’s basic needs are covered (food, water, shelter etc.) they tend to be primarily motivated by things that are not financial. People identify and support causes and projects that provide them with a sense of purpose. People define themselves and establish and sustain their identity and sense of self through their actions. People get a sense of meaning from doing things that matter to them. People find a sense of belonging by being a part of something bigger than themselves. For a popular account of much of the research behind these ideas see Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us for some of the more substantive and academic research on the subject see essays in The Handbook of Competence and Motivation and Csíkszentmihályi’s work on Flow.

Projects that can mobilize these identities ( think genealogists, amateur astronomers, philatelists, railfans, etc) and senses of purpose and offer a way for people to make meaningful contributions (far from exploiting people) provide us with the kinds of things we define ourselves by. We are what we do, or at least we are the stories we tell others about what we do. The person who started rationing out their work transcribing those manuscripts did so because that work was part of how they defined themselves.

This is one of the places where Libraries, Archives and Museums have the most to offer. As stewards of cultural memory these institutions have a strong sense of purpose and their explicit mission is to serve the public good. When we take seriously this call, and think about what the collections of culture heritage institutions represent, instead of crowdsourcing representing a kind of exploitation for labor it has the possibility to be a way in which cultural heritage institutions connect with and provide meaning full experiences with the past.

Leave a comment